Review: "The Seed of the Sacred Fig"

- Jennifer Green

- Dec 17, 2024

- 3 min read

Iranian film The Seed of the Sacred Fig opens with a description of a plant whose own seeds grow to eventually strangle its host tree. In the film, children grow to eventually question their parents’ values – and, in the case here of Iran, call for the overthrow of an authoritarian government, stifling social traditions and use of violence against citizens.

What makes this film so impactful is the way one family’s story is developed to reflect and embody the realities of an entire society. Tellingly, last spring, director Mohammad Rasoulof was sentenced to eight years in prison in Iran and other punishments for his critical work. He concluded shooting this film clandestinely and, in a tale worthy of its own film, made his way out of Iran on foot. He now resides in exile in Germany, which nominated Sacred Fig to represent it in this year’s International Oscar race. The film also screened in competition at last May’s Cannes Film Festival.

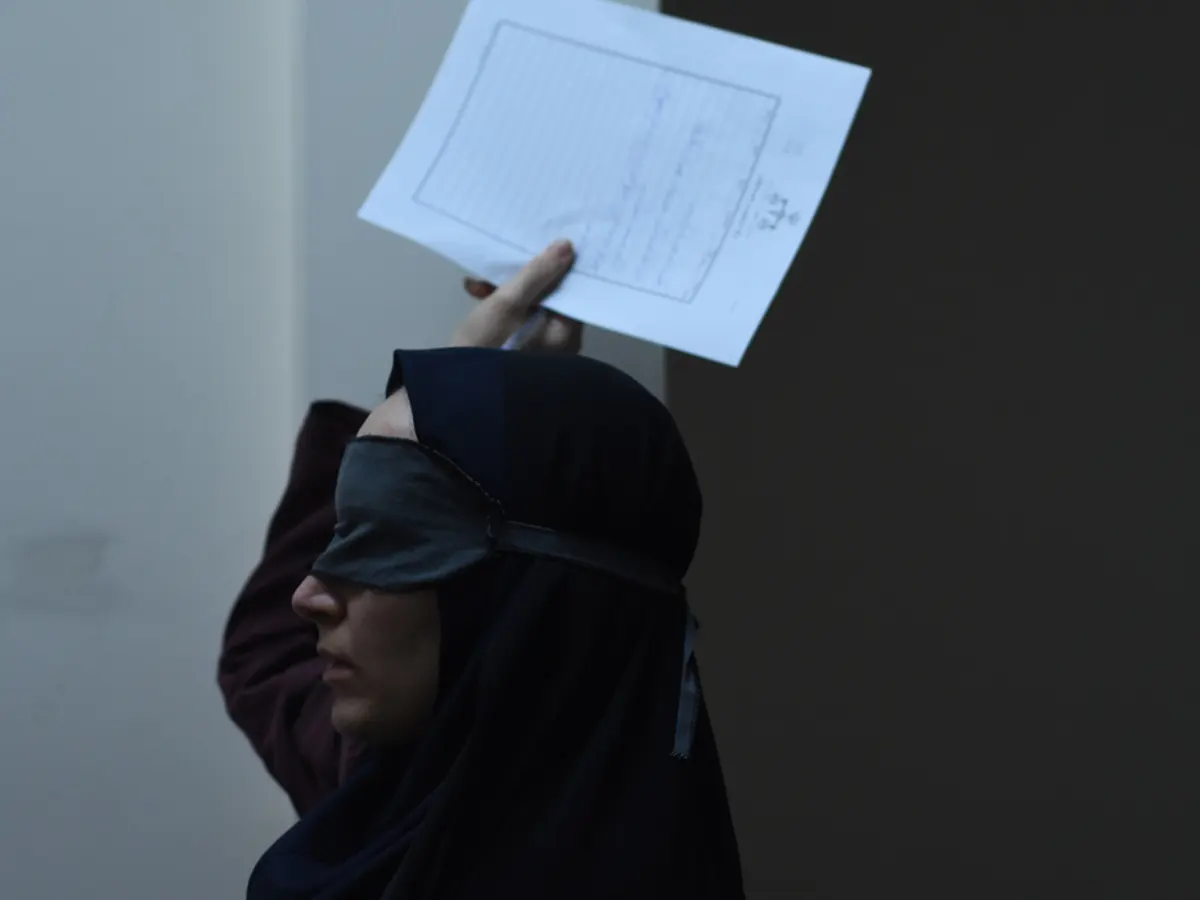

In Sacred Fig, Rasoulof incorporates actual video footage, mostly shot on cell phones (so, watched and exchanged appropriately by young characters on their phones) from the mass protests that gripped Tehran in 2022. The real-life suspicious death at a police station of 22-year-old protestor Mahsa Amini is also incorporated into the storyline. In the film, the older daughter Rezvan’s (Mahsa Rostami) best friend Sadaf (Niousha Akhshi) gets similarly caught up in protests, violently shot and unjustly arrested. The rising tension on the streets seeps into the household and family.

Dad Iman (Missagh Zareh) has just been promoted to a government investigator role. He is working morning until night handling protestor arrests, despite his initial discomfort at having to rush investigations and even death sentences. Mom Najmeh (Soheila Golestani) is mostly focused on the improvements the promotion will bring to their lifestyle – a bigger apartment, a new dishwasher – and to making sure her daughters comply with morality rules for women in public. She serves her husband’s every request and need.

When Iman’s government-issued gun goes missing in their home, and the family’s address gets published online, dad begins feeling increasingly paranoid. Rezvan and younger sister Sana (Setareh Maleki) empathize with the protestors’ demands, undermining everything their father stands for. Najmeh, initially stuck in the middle and supportive of both her husband and the propaganda coming through the news, eventually has to take a side when events start slipping out of control.

The first half the film spends significant time on developing these characters. Two intimate scenes in particular are set to haunting music and given significant screen time – Najmeh removing buckshots from Sadaf’s face and dropping them, slow-motion, into a bloodied sink, and later Najmeh painstakingly grooming her husband’s face and hair. Najmeh is the cornerstone between facets of her family – between genders and generations. She is both caretaker and protector.

She has a line in the film where she tells her daughters she’s tried to shield them from their father’s rougher side, which seems intended to explain his eventual unraveling. In earlier scenes, Iman seems genuinely troubled by the ethically questionable requirements in his new job, and he admits to his wife in a private late-night conversation that he’d like to give his grown daughters a hug and a kiss. Later, he subjects his family to interrogations and detentions like the inspector he has become.

His unraveling in the latter half of the film is suspenseful, with final cat-and-mouse scenes playing out in an especially memorable location, but the ending could feel somewhat forced upon these characters. However, this meshes with their intended embodiment of the polarization between generations and genders in Iran, and the unraveling of traditional values and social mores, in particular women taking back power and agency.

This review originally ran on AWFJ.org

Images courtesy of Neon

Comments